Kaare Frang

Eyes Holding Hands

Installation view of Eyes Holding Hands by Kåre Frang at Lagune Ouest, Copenhagen

Advertisement

Oslo. 2024. Pigment ink in polymer modified plaster, UV protective acrylic sealer, artist frame made from elm. 174,7 x 119 cm

Stickers in sunlight. 2024. Pigment ink in polymer modified plaster, UV protective acrylic sealer, artist frame made from elm. 174,7 x 119 cm

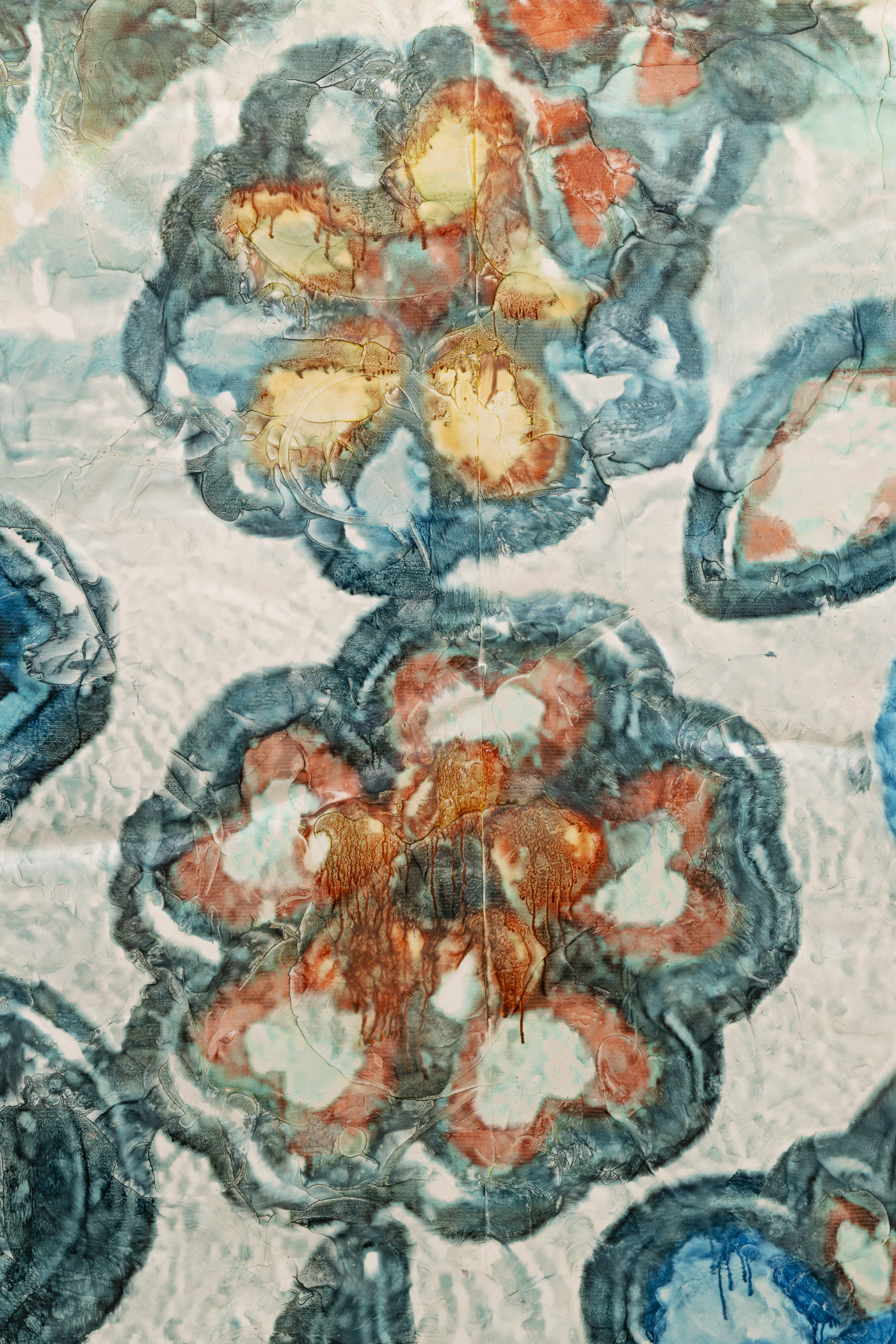

Stickers in sunlight, (detail)

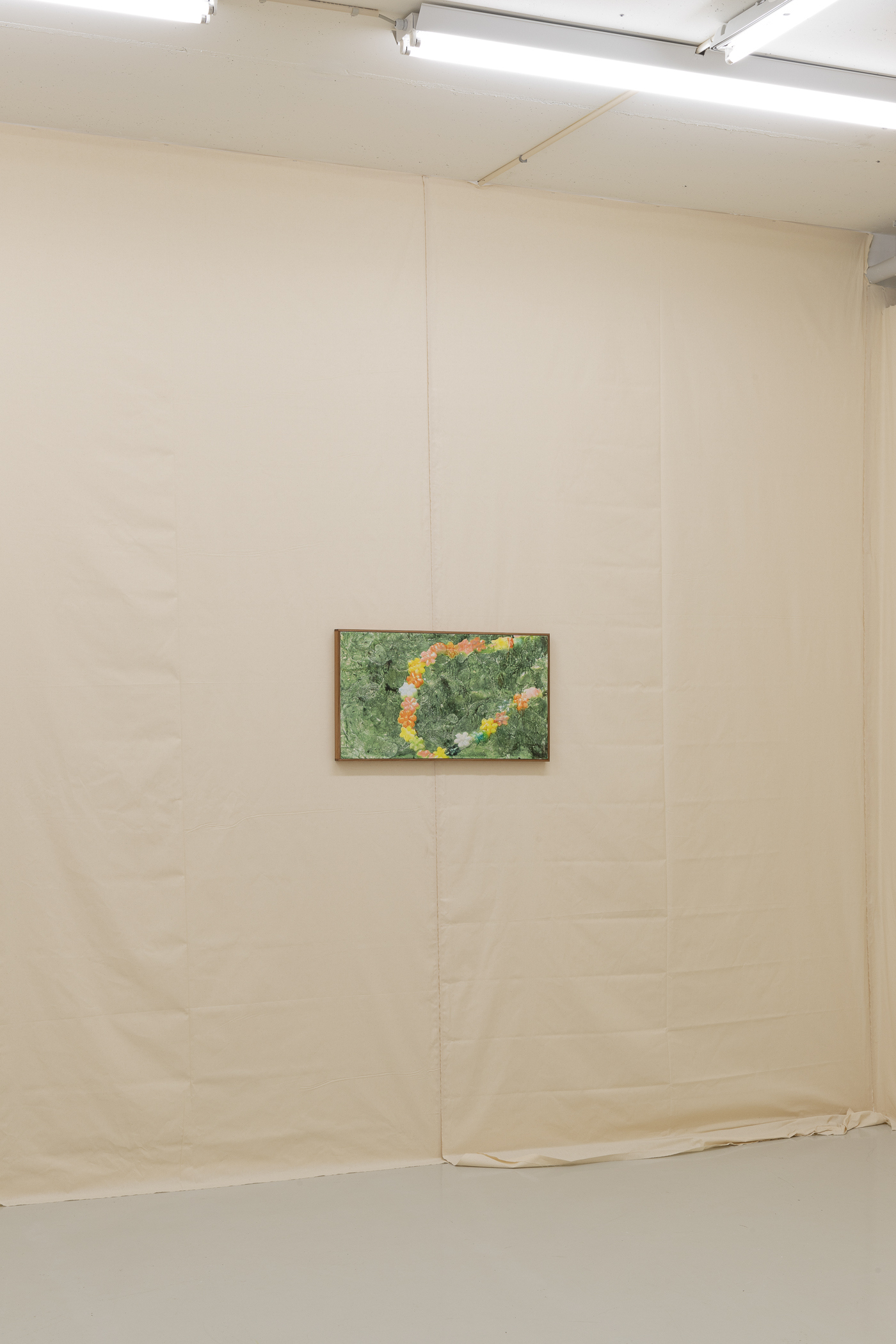

Installation view

Hands. 2024. Pigment ink in polymer modified plaster, UV protective acrylic sealer, varnish. 18 x 26 cm

Hands, (detail)

Installation view

The pearl necklace that disappeared. 2024. Pigment ink in polymer modified plaster, UV protective acrylic sealer, artist frame made from elm. 42,5 x 74,5 cm

Installation view

Flea market in Venice. 2024. Pigment ink in polymer modified plaster, UV protective acrylic sealer, artist frame made from elm. 37,3 x 49,3 cm

Installation view

Fika. 2024. Pigment ink in polymer modified plaster, UV protective acrylic sealer, artist frame made from elm. 174,7 x 119 cm

Installation view

Installation view

The pearl necklace that disappeared (three pearls in water). 2024. Pigment ink in polymer modified plaster, UV protective acrylic sealer, artist frame made from elm. 54,7 x 74 cm

The pearl necklace that disappeared (three pearls in water), (detail)

Installation view

The view just before returning home. 2024. Pigment ink in polymer modified plaster, UV protective acrylic sealer, artist frame made from elm. 31,5 x 42,2 cm

Installation view

PUBLIC INVITED

To LAGUNE OUEST,

independent purveyor of innovative artifacts, propagator of trailblazing ideas, and advocate of top-quality artists and their works, located one flight below the surface at Tagensvej 85 in Copenhagen, Denmark,

To witness

EYES HOLDING HANDS

the curious and amusing exhibition of picture-objects manufactured by Kåre Frang,

on display from the Ninth of August until the Seventh of September, in the year Two Thousand and Twenty-four, common era.

Assuming an alliance between matter and memory,

the EXPOSITION

publicises the results of true experiments accomplished in the artist’s Frederiksberg studio, utilizing a novel material process concocted and contrived by Frang himself and deduced from observation and practice. In each of the specimens, the artisan first prints digital photographic images on an impermeable temporary surface, leaving a raw puddle of ink expressing the referent. Working from behind the pictures, he then lathers on layers of liquid acrylic polymer plaster that absorbs and fuses with the chroma, distorting the depiction within by imposing a painterly, tactile, and textured topography. The images are thus rendered within the pictorial ground not atop it. Each object is framed in the finest elm and available for appraisal and acquisition. The remarkable products of this process unite the muses by mimicking and conflating properties of a diversity of fine arts media (painting, photography, sculpture, relief etc.), accentuating, perhaps above all, the muddy terrain of picturemaking today.

This exercise in the mediation of images taps into the artist’s photo stream, drawing selections from an archive of perfunctory mobile phone snapshots accumulated from coincidental encounters and sensitized attention. The repertoire of the images is a litany of mundane, trivial phenomena observed in everyday life – a packet of stickers, crows eating cake, a display of glassware at a flea market, a Danish landscape, etcetera…They are personal, fleeting, and commonplace, loaded with intimate memories such as the loss of a children’s necklace, yet also are as purposeless and inconsequential as any other image archive on one’s phone.

Indeed, digital photography is more akin to data collection than capturing a ‘decisive moment’. Today, the very act of taking a photograph is a mnemonic routine, where feeling and recording are simultaneous. A recording of the click of a camera shutter provides a feeling of being in the moment and capturing it for future review, an almost automatic externalization of memory that is perhaps more of a sign of memory’s decay rather than its longevity. These images are closer to notes than photographs, not only marking the particular paths of the artist, but also betraying his peripatetic perspective and peculiar pictorial proclivities. Specific objects and places are rendered through the close-up, the landscape, the still life, and other generic structures. On that account, the works accordingly can be situated in the artist’s larger artistic endeavour of identifying simplified representations in the everyday as sites of change and fragility, using familiar signs as a form of abstract knowledge building and making sense in a tumultuous world. Yet here, the familiar compositional conventions demonstrated in the all-over images suggests a universal grammar for imaging and imagining the world around us, where our memory assemblages and apprehension of experience has now been entirely overtaken by the omnipresence of the photographic and its tropes. It would be erroneous to refer to the images as photographs—no chemical, optical, or mechanical process has been used—yet they are nevertheless products of a photographic view of the world.

Modestly humane, sentimental, and unpretentious, the series is an attempt to relay a sense of true, faithful, and embodied presence at a time of hypermediation and the incessant flickering ephemerality of images, a special way of maintaining and carrying on a contact with objects and events. The artist delays the “fixing” of the image, lingering with, developing, and cultivating the pictures, leaving them wet, fresh, al fresco, as long as possible. By implicating water in his process, the artist aligns plaster and photography through their prehistory and their material hydraulics, their essential wetness, exposing a certain archaic liquid intelligence at the genesis of form. The intimate contact of ink and plaster happens at the moment of their molten materiality, generating a primordial ooze of plasmatic potentiality, a formless mass that exists prior to any relation, but also staging a transfer, or rather diffusion, of information. A link is established as the materials transition from one state to another, where the latent, virtual potential image finds material expression. This contamination reroutes the indexical transfer of the photograph (a long moribund notion) through the ancient principles of sympathetic magic (which operate under the superstitious laws of resemblance and contagious contact to transport powers and influence from one entity to the next), producing an analogical chain that connects the object or space depicted to the extant spectator.

The bastard bas-reliefs provide a sense of handcrafted uniqueness, a trace of the artist’s hand. The making of the works is anything but floundering: the procedure is tailor-made to solicit the fortuitous accident, the quirk of circumstance or process, that prevents the artist from falling back into the trap of the tried, tested, or true. Managing the material rather than controlling it, Frang introduces something aleatory to essentially receptive media. The use of plaster evokes architecture, preparatory moulds in sculpture making, and processes of replication, while also drawing a line to the relics and frescos of antiquity. As they congeal and dry, the reliefs are not calcified, but instead plasticized, where the polymer binder in the muddy mix gives the images an added rigidity and shine unalike the gritty particles of plaster or pixels. Like a bagged apple at a grocery store, the plastic is used here to preserve, to keep freshness. Yet the inventive technique is not a filter, a layer of code or prophylactic lining added on top of the image, a ‘special effect’. Instead, the procedure initiates a fusion of figure and ground, synthesizing surface and support and encasing the images akin to Andre Bazin’s statement that photography preserves fragments of the past “like flies in amber”.

While the effect may be reminiscent of the mass printing of photographic images on the surfaces of commodities, the material experiments have exceeded a direct indexical visual use, and created, literally and metaphorically, another dimension to the image filling the surface from edge to edge in glacial formations. This augmented topology introduces a turbulent texture to the pictures, full of subtleties and disfigurements, drips, indentations, compound curvatures, ridges, crevices, and fascinating fasciations. As if frozen mid-undulation, a tension is established between the surfaces of the objects represented and the congealed and coagulated façade, at once degrading and accentuating the image. Harboring hidden operations that circumscribe what can be imaged and how, the objects thwart the false transparency of facts and imposes a sensual quality, a material weight. This added swampy surface is superficial yet captivating, recalling Friedrich Nietzsche’s condemnation that “they muddy the water, to make it seem deep.”

The picture-objects invite a baffling vision, dispersing effects across the picture plane so as to disintegrate and disable identification, providing a feeling of distance however close and familiar the images might be. This corruption of the pictures incites a bodily relationship between the spectator and the image, affirming a haptic visuality (as the exhibition title suggests), a cognitive modality that exploits a larger somatic range of perception enmeshed with subjective, embodied and sensuous interactions. This contingency calls upon the viewer to engage in imaginative construction, and both within the production process, and in their unrelenting all-over quality and human-sized scale, there is an integral logic of absorption imposing an ontological force. The works seem to capture an experience of the world as resisting the mind’s organization of sensation into a coherent, cognitively well-ordered reality, and initiates synthetic ‘sense-making’ capacities in the viewer. Here, it is not merely the image qua image that is the site of meaning, but its material and presentational form and degeneration. They illustrate a dissolution of objects and images that bind us to a common world, while also elaborating the mnemonic potency of matter.

Furnishing fresh illustrations of old principles, EYES HOLDING HANDS is a demonstration of Frang’s sensuous, mutable thinking, a journey into the viscosity of memory and the attachments and contaminations that connect objects, images, and experience. As Henri Bergson reminds us:

“To picture is not to remember.”

This critical communique has undergone serious consideration by yours in service, Post Brothers.

Post Brothers