Archive

2021

KubaParis

Take Your Time

Location

Boutwell SchabrowskyDate

05.05 –11.06.2021Photography

Max Boutwell Draper, Julia MilbergerSubheadline

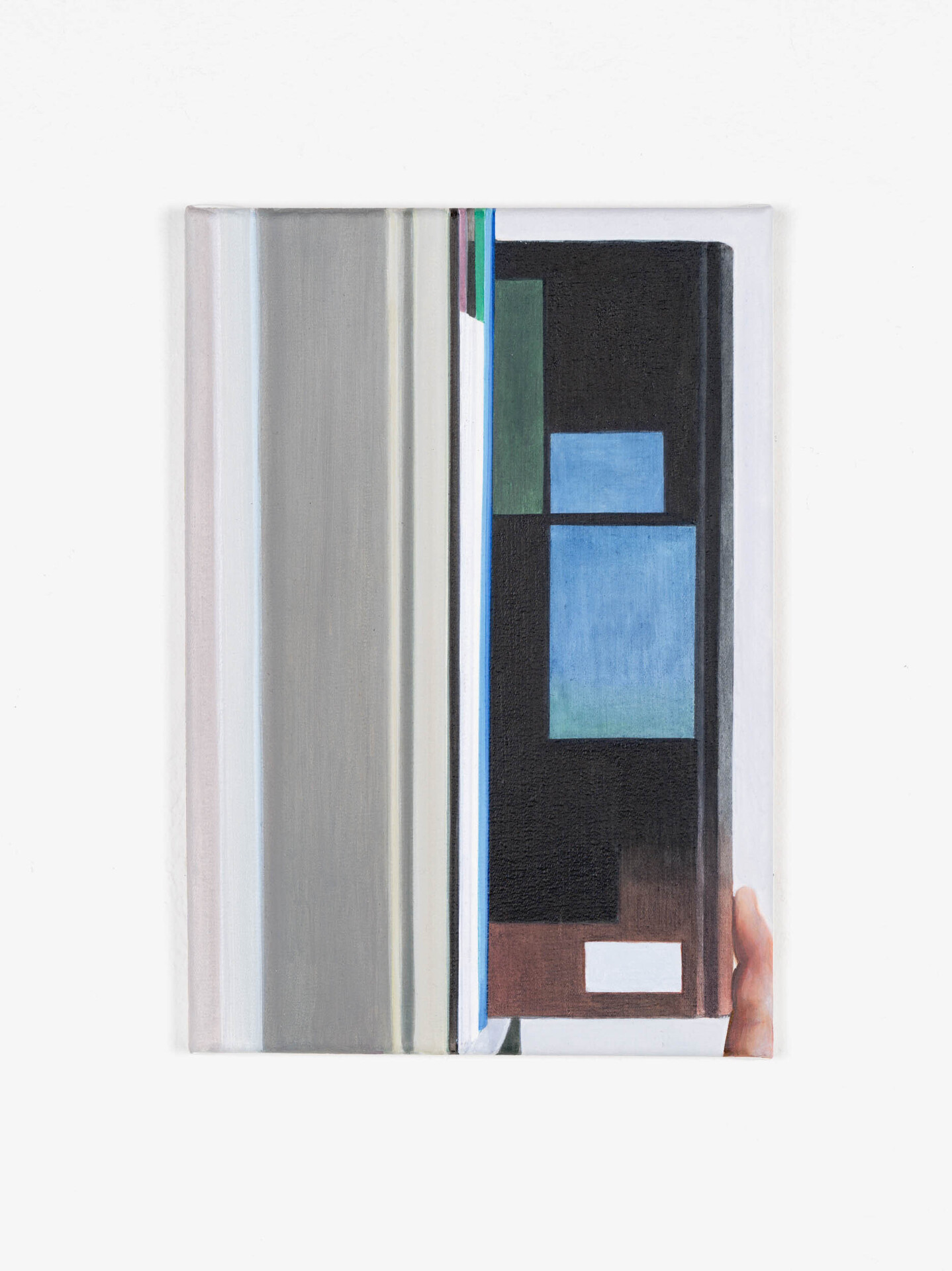

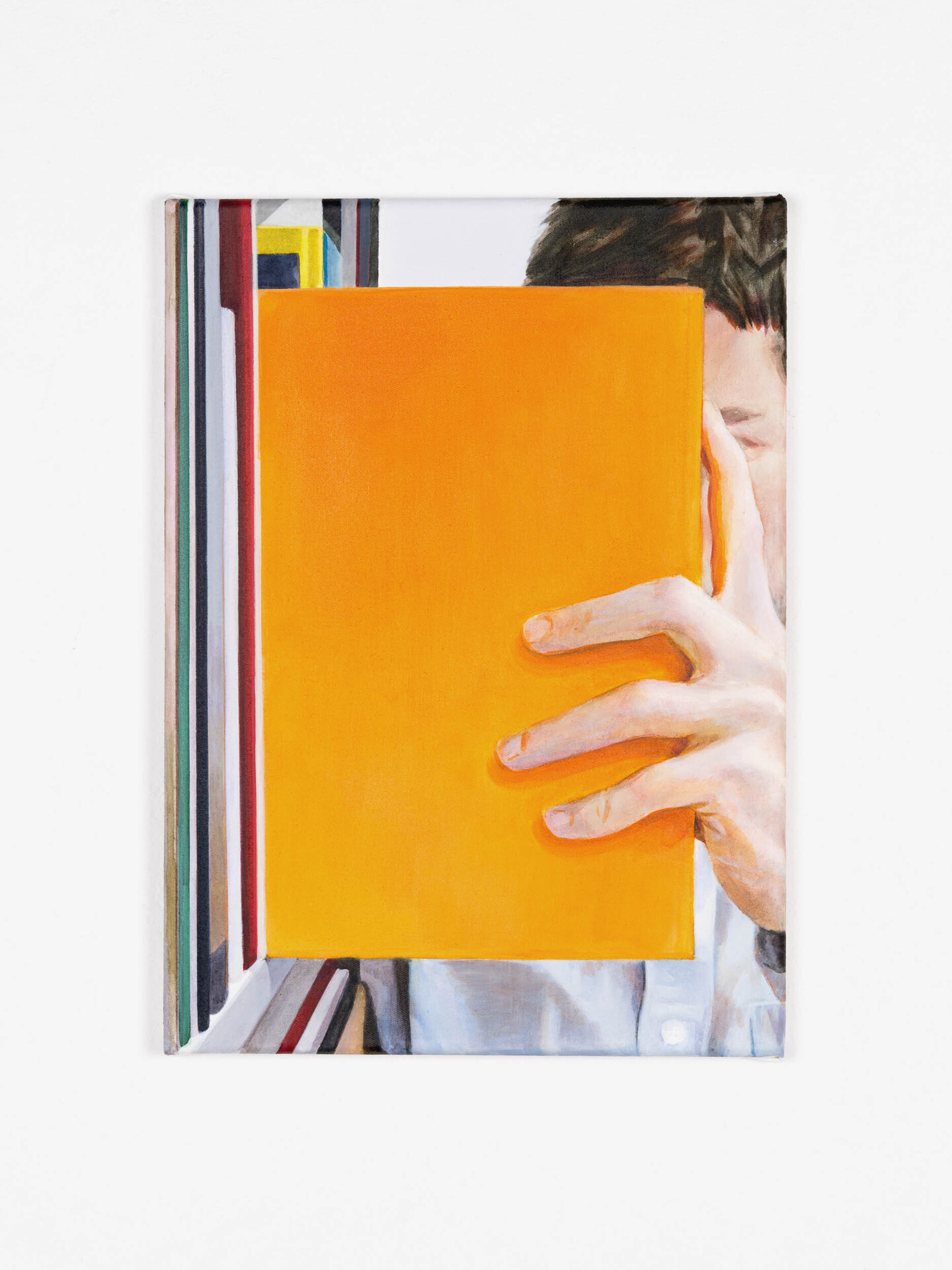

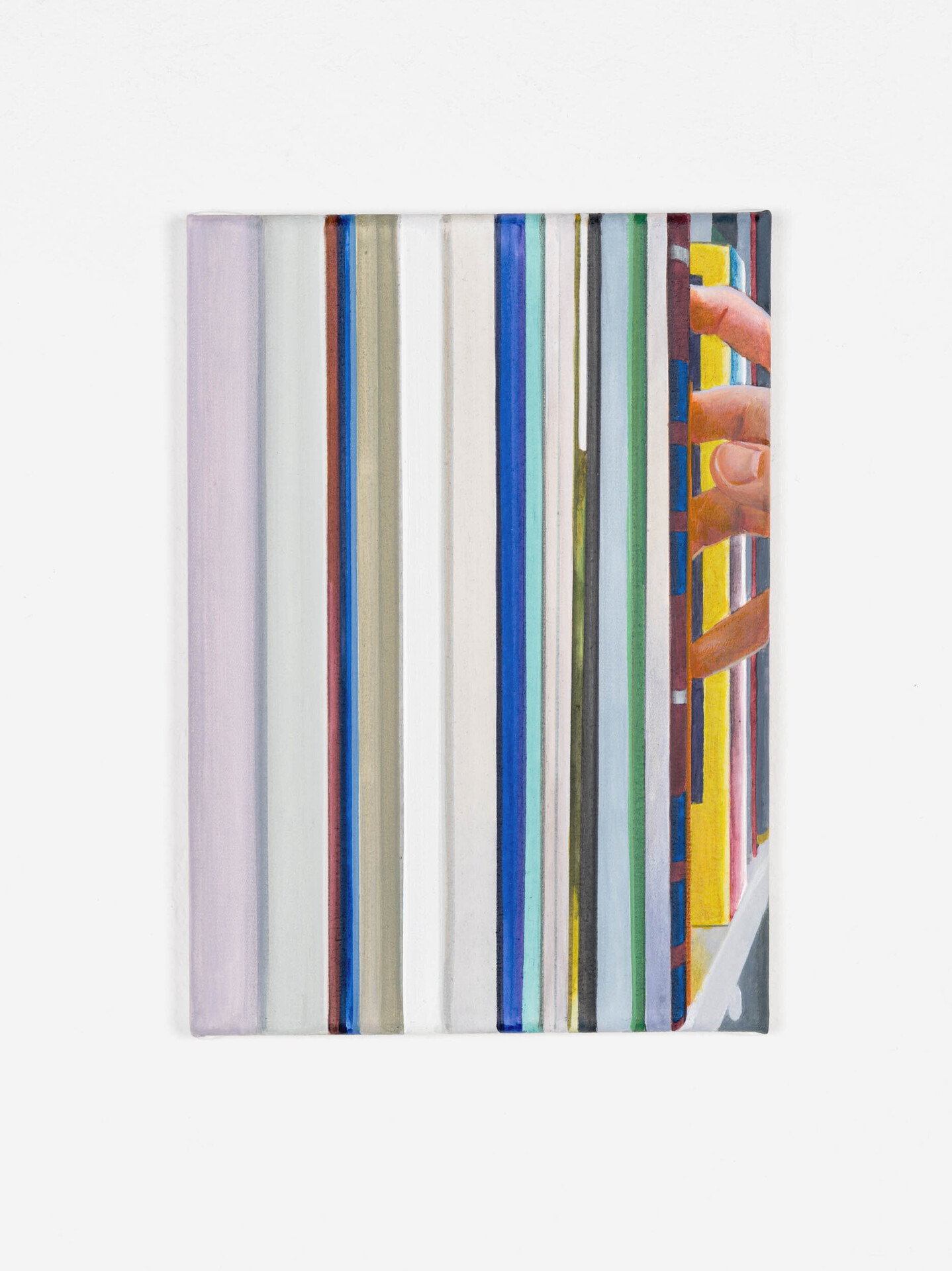

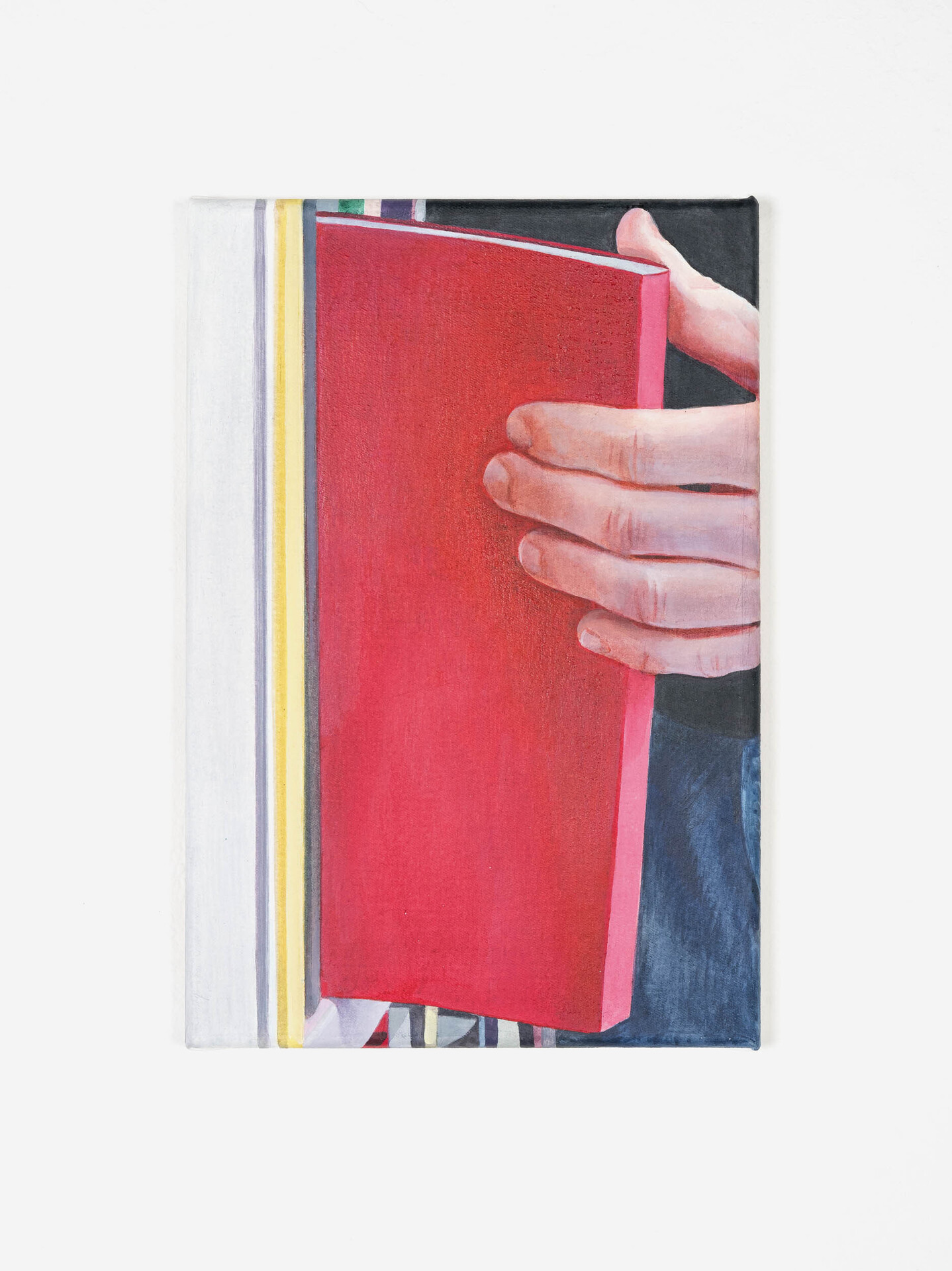

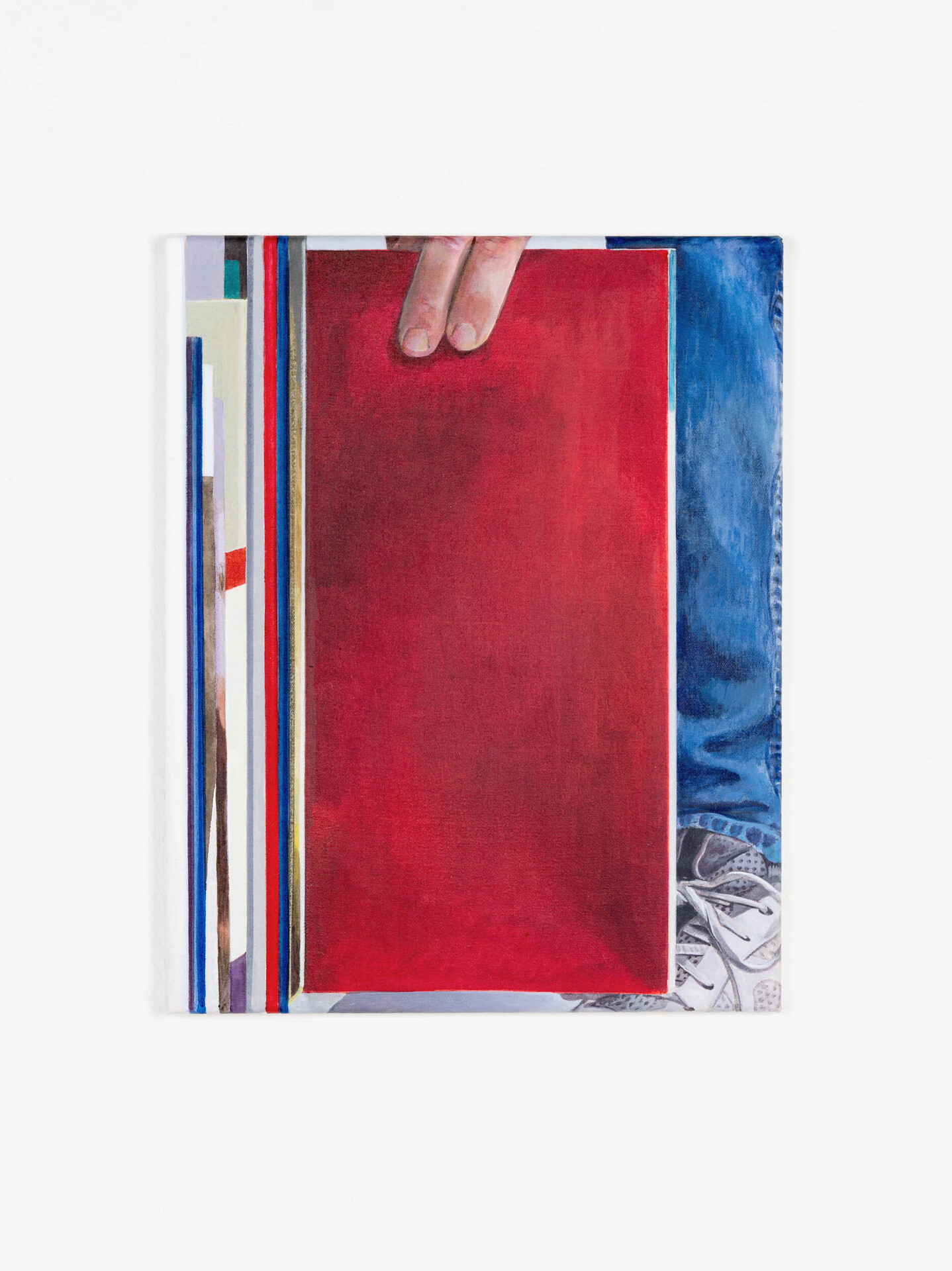

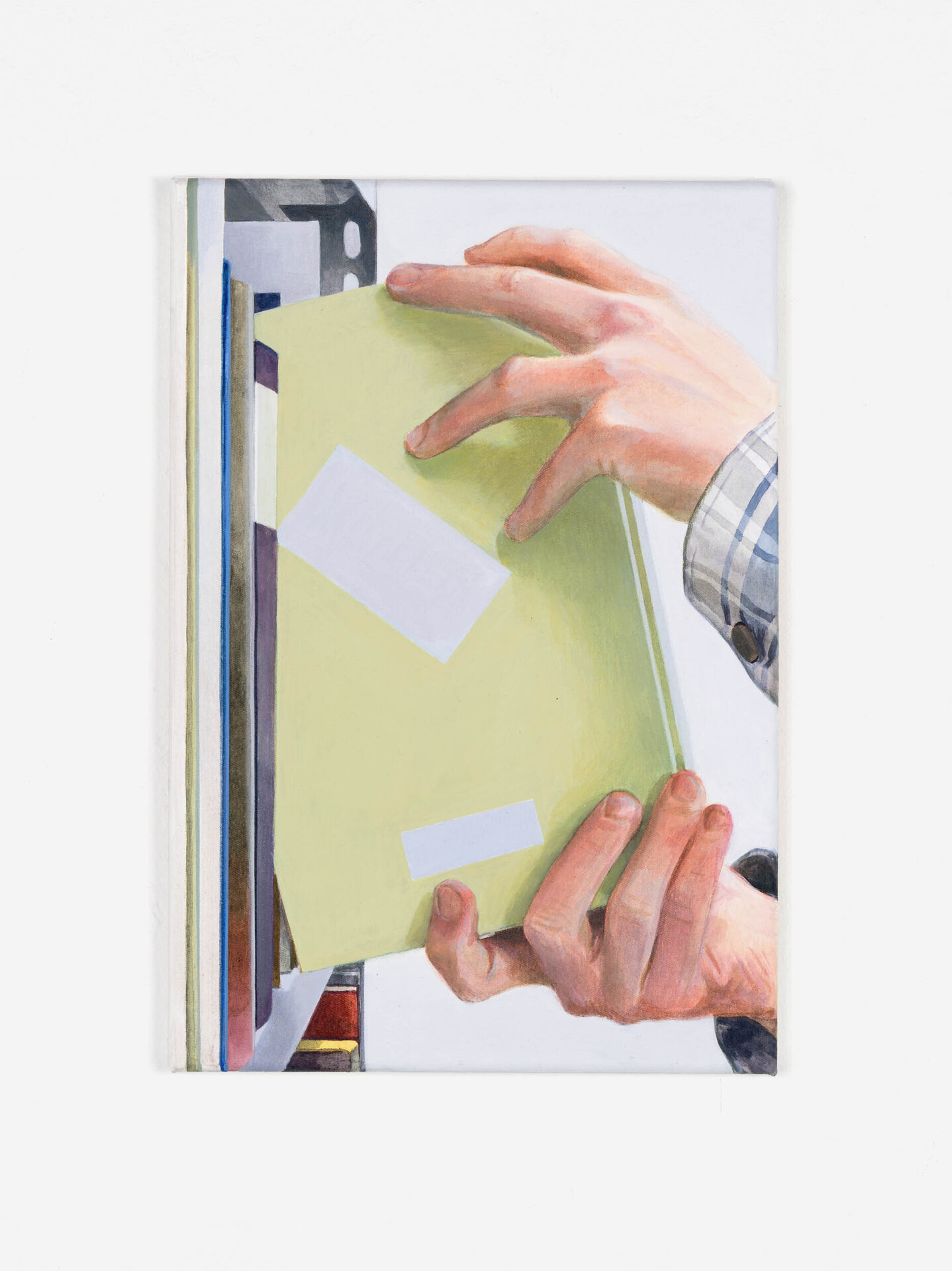

Boutwell Schabrowsky is pleased to present the first solo exhibition of Jonah Gebka, entitled "Take Your Time". In his presentation, the artist focuses on a new series of 40 paintings each depicting a book being taken out of or put back on to a shelf by a hand or a pair of hands. The paintings are installed in a continous band across the gallery space. The exhibition is accompanied by two texts and a film. The essays "The Space of Translation" by Peter Westwood and "Repeatedly Reaching For Answers Not Quite to Grasp" by Johanna Strobel deal with themes and ideas related to the paintings and their motives. The film "How To" by Max Boutwell Draper and Jonah Gebka documents the step-by-step process, taken by the artist, as he prepares for his solo exhibition at Boutwell Schabrowsky, Munich.Text

"The Space of Translation" by Peter Westwood

Writing on the paintings of Jonah Gebka

The act of making a translation might be thought of as seeking the real or endeavoring to find veracity. However, given its interpretive nature, a translation, and its original text can also be thought of as slightly uneven parallel acquaintances, cohabiting a space made discernable for its atmosphere of variation and difference. Positing translation as essentially embedded within every act of speech, Mexican poet Octavia Paz, asserts that primacy and stability within a text are always in doubt. Paz questions the hierarchical relationships between original and translation, claiming that ‘...all texts are original because every text is distinctive.’ (Barnstone 1992, p. 5). The idea that translation is a shifting space, prompts me to reflect on the way that all things within the world move through cycles of translation and reinterpretation. This is how our current times manifest – wherein versions and remakings seem to frequently inhabit most of what we encounter. Our period could be considered as forming through changing viewpoints, and interpretations, propelled through partial truths and fictions, circulated through social media, conventional media, and partisan politics (Rauch, 2020). Hence, in writing this during a pandemic, reflecting on how we might decipher what we see and hear, the phrase ‘uncertain, inconclusive shifting realities’ appositely emerges to typify the experience of our times.

Jonah Gebka’s exhibition, "Take Your Time", presents us with the uncertainty of seeking a decisive or conclusive moment. His paintings appear to mediate on the idea of searching and locating within a regulated but ever-changing space. In fact, the images in each of his works appear as transitioning moments, instances where a person, decisively, or inconclusively, extends a hand to remove, or return, a text from a library. Libraries are regulated spaces, however, the disembodied actions of the hands that Gebka depicts seem unfixed, as if he is playing at the edge of order and disorder or evoking the randomness we experience in the passing of time.

Gebka represents hands enfolding books that are devoid of the signs and markings which might normally assist us in pinpointing their content. In fact, rather than being solely representations of books, the lack of any identifying features on each text – apart from the individual colour of book jackets – encourages us to consider the books as geometric shapes within a painting. In a roundabout way, this brings to mind Gerhard Richter’s frequent repudiations of the differences between abstraction and representation in painting (Elger & Obrist 1973, p. 72), and the inherent questioning this conjures in relation to the stability of representational painting. Sequenced as they are as a grouping of moments, Gebka’s paintings are equivocal, guiding us towards the undiluted visual sensation of colour and form as their eventual content. However, the imagery of Gebka’s paintings reflect on the conjectural nature of seeking, coupled with the physical act of looking – needless to say, a nucleus of painting.

Part of Gebka’s working method involves the process of photographically recording certain actions, which then filter through conscientious translations of the photograph into a painting. This is the space French philosopher Michel Foucault defined as the productive space between media (Soussloff, 2017), where a painting and a photograph, when intermingled in some way, enter into a state of between-ness: ‘... not a painting based on a photograph, nor a photograph made up to look like a painting, but an image caught in its trajectory from photograph to painting...’ (Hawker 2009, p. 272). Effectively, this is a translation from one source to another, where the solidity of each parallel acquaintance, photograph and painting, might be questioned. Gebka perceives his paintings as the translation of an image into a woven pattern where he is able to ponder the effect this translation may have on the original image – for Gebka, the recognition and sense of touch in painting becomes part of seeing (Weiland, 2020). Gebka’s paintings question the stability of representation as they evoke touch, intimacy and abstraction, where we in turn doubt that a book is simply a text, rather than a form, or a suggestion of moments in time. There is no doubt that we form narratives around the imagery in this work, and, in doing so, devise mutable associations. Although, his depictions of the selecting and returning of books seem to echo some of the uncertainty and repetitive nature of living, there is something recovering about eventually sidestepping these associations, to simply reside in the purely visual and abstract state of these paintings.

While we are mindful of the veracity of this visual abstract state, we hold a dual awareness within us between abstraction and the various associations we have in relation to the imagery. Each item being removed in the library, presumably taken into the world by someone, anyone, and then returned, makes us aware of the everyday. Beyond the banality of this act, we are reminded that our lives are composed and directed by temporal repetitions, iterative moments of being. This is ordinary time, where we return perpetually, repeating the moments in our lives that form and accumulate. Gebka’s works evoke the layered accumulations of things, of time, events, information and histories, remembering and forgetting – the veracity of living, which in the end might just be captured by the purity of a moment where we look, and are arrested by the sensation and experience of the purely visual.

Notes:

Barnstone, W. (1993) The poetics of translation: history, theory, practice, Yale University Press, London.

Elger, D., & Obrist, H., (eds). (2007). ‘Richter, interview with Irmeline Lebeer, 1973’, Gerhard Richter – writings 1961 – 2007. London: Thames and Hudson.

Hawker, R. (2009). ‘Idiom post-medium: Richter painting photography’, Oxford Art Journal, Vol. 32, No. 2 Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Rauch, J. (2020). ‘What Trump has done to America: Three ways the outgoing president’s postelection fight changed the political landscape’, Ideas, The Atlantic Magazine, Boston, Massachusetts.

Soussloff, C. (2017) Foucault on painting, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis.

Weiland, M. (2020) Artist conversation: Max Weiland talks with Jonah Gebka. Künstler Künstlerin Artist Conversation (online).

"Repeatedly Reaching For Answers Not Quite to Grasp" by Johanna Strobel

Figuratively speaking I imagine Jonah’s paintings being on the high noon position of a circular line of image distribution; as if his works would surface from a referential stock archive to take a deep breath before becoming references for subsequent works or diving back as documentation jpegs into Hito Steyerl’s swarm circulation of the poor image where there is no tracing back to a primary original anymore.

While Jonah’s handcrafted paintings are inherently as authentic and unique as can be, their motifs come from a long lineage of simultaneous reproductions of similar versions and reaffirmations that don’t allow a tracing back of what references what.

The aesthetics of stock photography his motifs incorporate (whether because they actually are, or mimic stock images) produces a sense of apparent neutrality through ubiquity and conformity, when of course this imagery actually reproduces corporate monoculture.

But Jonah doesn’t use these images as subject matter. He borrows their aesthetics and pictorial content which he utilizes and transforms into patterns and reappearing themes. The recurring and repeated motifs serve conceptual purposes beyond of what is represented and produce meaning in an extended context. They open up a mental space inviting the viewer not to act but to pause and hand themselves over to contemplate the given moment stretched by a frozen action.

The body of work presented at the gallery depicts hands pulling books from, or putting them back onto shelves. The gestures of the respective painted hands are ambiguous. Though they are repetitive, the gestures are not identical. Each painting is unique in composition, size and color while the motif, a book pulled out / put back on a shelf by one or a pair of hands, stays the same.

The covers of the books on the shelves are blank and mainly monochrome. They neither show text nor images. The books’ contents are emptied out. They become props for the hands; only the gesture of taking the books out of, or putting them back onto the shelf remains. But without the books’ content this gesture loses its meaning as well. Books without titles and covers cannot be indexed and put into order. Empty books contain no knowledge or information. There is no point in pulling an empty book from a shelf; nothing can be looked up. Maybe the hands are frozen or paused in the moment of realization, that there is no information to be retrieved and so in the second after that realization, the book will be pushed back in line again to the empty others on the shelf.

The shared motif of the paintings is repeated over and over again but still the paintings are not reproducing or copying each other. All the works are painted after composed referential photos, so in that sense they are reproductions of preceding images and thus can be simultaneously seen as copies and unique originals.

Within their variety they are not redundant but they seem to be retaken versions of one another without hierarchy and referential order. The paintings follow each other in their serial progression and thus avoid the inferences of relational composition. This undermining of referential ordering through repetition subverts representation, while the specificity of the repeated motif, the individual gestures, produces tension between these works as non-identical but still copied originals.

Today, as most books are probably written and designed using computers, the manuscript of a book is only a digital file, which for now leaves the question of the unique original of a book unanswered (probably at least until that file is minted as an nft and sold by amazon). Books as such, if they are part of the same edition, can be described as multiple identical copied originals while Jonah’s paintings could in the above sense be seen as unique non-identical original copies.

All images and texts courtesy of:

Jonah Gebka, Boutwell Schabrowsky, Munich, VG-Bildkunst, Bonn, and the authors.

Peter Westwood, Johanna Strobel